Melissa Jonson-Reid, PhD Brett Drake, PhD, Catherine Cobetto, Maria Gandarilla Ocampo

Washington University in St Louis

According to various news articles, child abuse and neglect hotlines around the country are reporting dramatic declines in the last few weeks.

- Colorado down by more than 1/3 from same time last year (Gliha, 2020)

- Connecticut dropped 70% (Thomas, 2020)

- Florida reports down 11% between January and February (LaGrone, 2020)

- Illinois down by nearly half (Eldeib, 2020)

- Missouri down 50% since March 11 (Bauer, 2020)

- Oregon down 70% in past month (Powell, 2020)

- Washington State dropped 42% a week after school closures (Pauly, 2020)

- Texas calls dropped 21% between February and mid-March (Platoff, 2020)

Normally a decrease in calls about alleged child abuse and neglect (or maltreatment) would be a welcome start to child abuse prevention month, but the context of current declines is worrisome. Let’s explore why. First, it is important to understand where reports about child maltreatment come from. Child protection is a form of emergency response that operates much like the fire department. Calls of concern are made to the state or county agency (hereafter called “Child Protective Services”: CPS). Those calls are assessed to see if the concern meets a state’s guidelines for a response. Nationally, about 33% of reports are made by voluntary reporters (neighbors, family, friends, self-reports, etc.). Of the remaining 67%, the largest group of reporters are educators followed closely by law enforcement/legal system (US DHHS, 2020) reporters.

So what is happening?

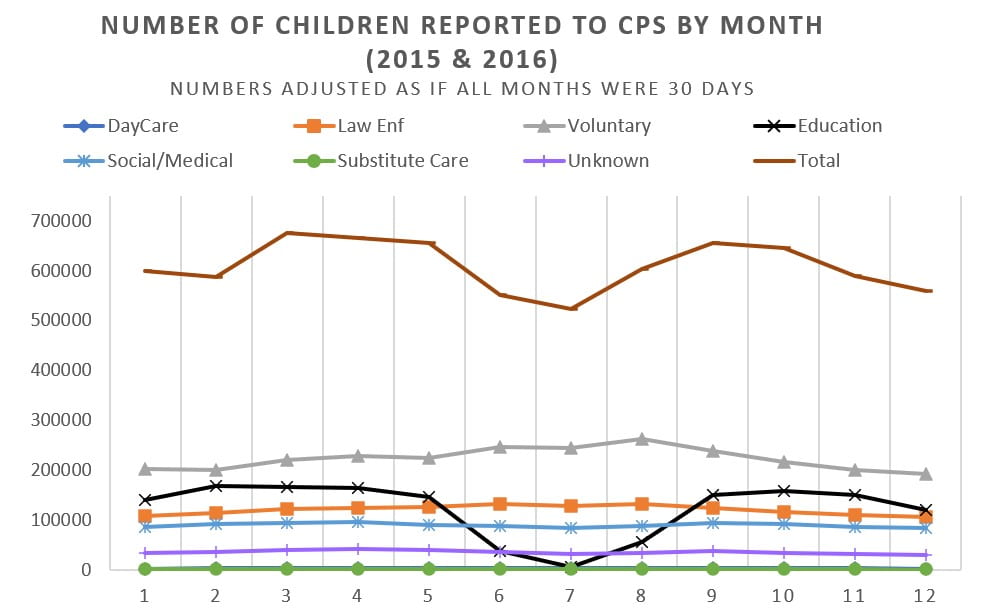

Two of the recent articles on COVID 19 and CPS reports raise the possibility that the declines might be due to school closures. Reports from educational personnel accounted for 20.5% of all reports in 2018 (DHHS, 2020). Seasonal fluctuations in reports do occur and some suggest recent trends are like what we might see each summer when schools are closed (Londberg, 2020; Pauly, 2020). This raises the question: “How big of a decline do we actually see in summer”? Looking at NCANDS Child File data for the number of children reported by month across 2015-2016 and adjusting for the different number of days per month, June and July are 7.6 and 7.2% of the total respectively while other months comprise between 7.8 (December) and 9.4% (March) each. Looking at May (9.1% of yearly reports) and July (7.6% of yearly reports, it seems we have a “Summer Drop” of about 16%. Reports from educators (see line for “Education” in Figure 1 below) do drop dramatically, but reports from other sources do not. Reports from permissive or voluntary reporters actually go up a little.

(Data from: NCANDS: 2015-2017 Child Files for calendar 2015 & 16. Drake & Jonson-Reid (2020) unpublished analyses).

The drops reported in the Florida and Texas articles might be within range of the summer dip, but the reported rates do not match with school closure policies. In Texas (Platoff, 2020) the drop was between February and mid-March, but Texas was not among the states to close all schools by mid-March (Nagel, 2020). The drop reported for Florida was between January and February (LaGrone, 2020)- long before school closures began in Florida (Nagel, 2020). Most, but not all, of the states reporting larger drops were following closures. If the normal drop from May to July is about 16%, that just isn’t high enough to explain the recent drops of referrals in the last month.

Should we be concerned?

Although space does not permit a full discussion, mandated reporting specifically and CPS more generally are frequently under fire for either intervening too much or too little. In a recent article, a reform advocate was quoted as saying this dip in reports is not a concern since many reports go uninvestigated anyway (Pauly, 2020). So how do we think about this? First, this statement is not universally true. Some states look into most calls (e.g., Alabama) and others “screen out” the majority (e.g., South Dakota) (US DHHS, 2019). Second, studies indicate that calls from mandated reporters are more likely to be screened in and substantiated (Mathews & Bross, 2008; Dumas, Elzinga-Marshall, Monahan, van Buren & Will, 2015; McDaniel, 2006). Some studies also suggest that the kind of concern and the level of detail reported is different for mandatory and voluntary reporters (Giovannoni, 1995; McDaniel 2006). Reports that are ultimately substantiated are more likely to receive services as well (Jonson-Reid et al., 2017). So, actually the reports we are not seeing now likely include a large number of those reports CPS would screen in.

Both theory and data suggest that stress and poverty are powerful contributors to child abuse and neglect (e.g., Conrad-Hiebner & Byram, 2020; Pelton, 2015; Yang, 2014). Unfortunately, the COVID-19 crisis is increasing both psychological stress and economic strain. Calls for help regarding basic needs like food are have increased dramatically (Schoenherr, 2020). Another article reported National Parent Helpline calls increasing 30% in a recent week including concerns about child care, food and other virus-related stressors (Hurt, Ball & Wedell, 2020). A large portion of recent calls to the National Domestic Violence Hotline cited the coronavirus as the reason for the call (Noveck, 2020). The very few studies we have on the impact on disasters on rates of child maltreatment suggest that there may be a link (Curtis, Miller & Berry, 2000; Keenan, Marshall, Nocera, et al. 2004).

While we are understandably focused on protecting those most vulnerable to the health effects of COVID 19 and providing immediate economic relief to those losing their jobs, we all need to seriously consider how fragile our current family support and child safety systems are. Following Hurricane Katrina some years ago there were calls made for creating disaster preparedness plans for child welfare (Berne, 2009; Daughtery & Blome, 2008). These were largely ignored. CPS workers do not receive Personal Protective Equipment, raising concerns about safely conducting investigations. Guidance in at least two states suggests calling first, and asking the family a few questions about COVID exposure. If a family may have been exposed, this guidance suggests relying on (in many cities already overwhelmed) law enforcement or EMS to go in the home to check on children (Missouri Department of Social Service, 2020; Illinois Department of Child and Family Services, 2020). Articles report both concerns for worker safety and concerns about the viability of providing in-home services remotely (Crary, 2020; Hardison, 2020; Kelly & Hansel, 2020). For children in foster care there are a number of additional problems. Many family members caring for children who enter foster care are older and more vulnerable to serious illness from the virus. Lack of access to services may make it harder for families who are trying to meet case plan goals to keep their families together (Crary, 2020: Kelly & Hansel, 2020; Sankaran, 2020). As Fred Wulczyn (2020) recently wrote, in the future we will need to be prepared to “increase our collective capacity for forgiveness.” Of course, that does not mean that nothing can be done now.

What can be done?

It is imperative that we do everything we can to be aware of the well-being of children in our communities. Social distancing need not prevent phone calls or emails to neighbors and family, help with groceries for those who cannot get out, and providing clear messages to families about where to get resources for parenting and meeting basic needs. In addition to the many regional efforts, Prevent Child Abuse America has a number of tips and resources related to COVID 19 for parents, children, service providers, and the community on their website: https://preventchildabuse.org/coronavirus-resources/. The United Way 2-1-1 call line is another excellent way of finding local resources. When a child is in danger, we will not be able to rely on the eyes of mandated reporters to call for help. Voluntary reporters may become the majority for a while. If you do not know how to report or don’t know your local hotline number, crisis counselors are available 24/7 at the ChildHelp National Child Abuse Hotline 1(800) 422-4453 and can guide you through the process. It is also important that we remember the strain this crisis is placing on the many people dedicated to serving the needs of families and protecting children who now find themselves in an utterly new and frightening context. Remote supervision can help, along with encouraging child welfare workers to reach out to mental health supports as needed.

Going forward, Sankaran (2020) and Wulczyn (2020) make a number of good points about the things we will need to address when the crisis subsides because of the current breakdown in services and court systems. I would suggest we also go a step further. After Katrina there were calls for crisis preparedness that were clearly not heeded. We need to be sure that we are not dismissing the lessons learned and put substantial plans and training in place for our child protection and family support systems (community agencies, courts, etc.). Finally, even before this crisis, the economic case for preventing child maltreatment was made clear (Fang et al., 2012; Peterson, Florence & Klevens, 2015). After we have addressed the immediate needs of our families, we should use this as a catalyst to bring together science and practice to build an effective system designed to alleviate both the material and psychosocial needs that get in the way of positive parenting and child well-being.

References

Bauer, L. (2020, Mar). Child abuse hotline calls plunge during coronavirus pandemic. Here’s why it’s a concern. Available online: https://www.kansascity.com/news/coronavirus/article241501811.html

Berne, R. (2009). Disaster Preparedness Resource Guide for Child Welfare Agencies. Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED507724.pdf

Conrad-Hiebner, A., & Byram, E. (2020). The temporal impact of economic insecurity on child maltreatment: a systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(1), 157-178.

Crary, N. (2020, Mar) Child welfare systems struggle during coronavirus pandemic. Available online https://chicago.suntimes.com/coronavirus/2020/3/28/21198168/child-welfare-coronavirus-pandemic

Curtis, T., Miller, B. C., & Berry, E. H. (2000). Changes in reports and incidence of child abuse following natural disasters. Child abuse & neglect, 24(9), 1151-1162.

Daughtery, L G., & Blome, W (2009). “Planning to plan: A process to involve child welfare agencies in disaster preparedness planning.” Journal of Community Practice 17(4), 483-501.

Dumas, A., Elzinga-Marshall, G., Monahan, B., van Buren, M., & Will, M. (2015). Child welfare screening in Wisconsin: An analysis of families screened out of child protective services and subsequently screened in. In Workshop in Public Affairs. Available online: https://lafollette.wisc.edu/research/publications/child-welfare-screening-in-wisconsin-an-analysis-of-families-screened-out-of-child-protective-services-and-subsequently-screened-in

Eldeib, D. (2020, Mar). Calls to Illinois’ child abuse hotline dropped by nearly half amid the spread of the coronavirus. Here’s why that’s not good news. Available online: https://www.propublica.org/article/illinois-dcfs-child-abuse-hotline-calls-coronavirus

Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S., & Mercy, J. A. (2012). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child abuse & neglect, 36(2), 156-165.

Giovannoni, J. M. (1995). Reports of child maltreatment from mandated and non-mandated reporters. Children and Youth Services Review, 17(4), 487-501.

Gliha, L. (2020, Mar). Colorado officials call reduction in child abuse hotline calls during COVID-19 pandemic concerning. Available online: https://kdvr.com/news/coronavirus/colorado-officials-call-reduction-in-child-abuse-hotline-calls-during-covid-19-pandemic-concerning/

Hardison, E. (2020, Mar) ‘The perfect storm:’ How COVID-19 has multiplied the risk for children in abusive households. Available online: https://www.penncapital-star.com/covid-19/the-perfect-storm-how-covid-19-has-multiplied-the-risk-for-children-in-abusive-households/

Hurt,S., Ball, A., & Wedell, K (2020, Mar) Children more at risk for abuse and neglect amid coronavirus pandemic, experts say. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/investigations/2020/03/21/coronavirus-pandemic-could-become-child-abuse-pandemic-experts-warn/2892923001/

Illinois Department of Child and Family Services (2020). Guidance to direct service staff. Available online: https://www2.illinois.gov/dcfs/brighterfutures/healthy/Documents/DCFS_Guidance_to_Direct_Service_Staff_031820.pdf

Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B., Kohl, P., Guo, S., Brown, D., McBride, T., … & Lewis, E. (2017). What do we really know about usual care child protective services?. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 222-229.

Keenan, H.T., Marshall, S.W., Nocera, M.A. et al. (2004). “Increased Incidence Of Inflicted Traumatic Brain Injury In Children After A Natural Disaster,” American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 26 (3): 189-193

Kelly, J. & Hansel, K (2020, Mar) Coronavirus: What Child Welfare Systems Need to Think About. Chronicle of Social Change. Available online https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/child-welfare-2/coronavirus-what-child-welfare-systems-need-to-think-about/41220

LaGrone, K. (2020, Mar). Child abuse calls are down amid COVID-19, worrying child advocates. Available online: https://www.abcactionnews.com/news/local-news/i-team-investigates/child-abuse-calls-are-down-amid-covid-19-worrying-child-advocates

Londberg, M. (2020, Mar). Coronavirus has put kids at risk of suffering abuse at home. Available online: https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2020/03/27/coronavirus-crisis-has-put-kids-risk-abuse-home-experts-warn/2909116001/

Mathews, B. P., & Bross, D. C. (2008). Mandated reporting is still a policy with reason: Empirical evidence and philosophical grounds. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32(5), 511-516.

McDaniel, M. (2006). In the eye of the beholder: The role of reporters in bringing families to the attention of child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(3), 306-324.

Missouri Department of Social Services (2020). Temporary policy in response to COVID-19. Available online: https://dss.mo.gov/covid-19/pdf/temporary-policy-in-Response-to-COVID-19.pdf

Nagel, D. (2020, Mar) More Than Half of All States Have Shut Down All of Their Schools. https://thejournal.com/articles/2020/03/16/more-major-education-systems-shut-down.aspx

Noveck, J. (2020, Mar). With isolation abuse activists fear an ‘explosive cocktail’ Available online: https://www.kpbs.org/news/2020/mar/26/isolation-abuse-activists-fear-explosive-cocktail/

Pauly, M. (2020, Mar.) School closures mean teachers aren’t reporting child abuse. The numbers are disturbing. Mother Jones. Available online: https://www.motherjones.com/coronavirus-updates/2020/03/reports-of-child-abuse-and-neglect-have-fallen-in-many-states-that-worries-some-experts/

Pelton, L. H. (2015). The continuing role of material factors in child maltreatment and placement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 41, 30-39.

Peterson, C., Florence, C., & Klevens, J. (2018). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States, 2015. Child abuse & neglect, 86, 178-183.

Powell, M. (2020, Mar.) Child abuse reports drop 70% in 1 month, leaving Oregon officials concerned. Available online: https://www.opb.org/news/article/child-abuse-reports-drop-70-in-one-month-leaving-oregon-officials-concerned/

Platoff, E. (2020, Mar). Out of sight, child abuse in Texas thought to be on the rise. Available online https://www.texastribune.org/2020/03/27/texas-coronavirus-child-abuse-likely-rise-risk/

Sankaran, V. (2020, Mar). The need for extraordinary efforts: Times of crisis reveal a system’s values. Chronicle of Social Change. Available online: https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/child-welfare-2/the-need-for-extraordinary-efforts-time-of-crisis-reveal-a-systems-values/41728

Schoenherr, N. (2020, Mar). Help line requests for food skyrocket as pandemic spreads. The Source. Available online: https://source.wustl.edu/2020/03/help-line-requests-for-food-skyrocket-as-pandemic-spreads/

Thomas, J. (2020, Mar). Connecticut’s most vulnerable children even more at risk during coronavirus crisis. Available online: https://ctmirror.org/2020/03/23/connecticuts-most-vulnerable-children-even-more-at-risk-during-coronavirus-crisis/

US DHHS, Administration of Children and Families (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2018

Wulczyn, F. (2020, Mar). Looking ahead: The nation’s child welfare systems after Coronavirus. Chronicle of Social Change. Available online: https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/child-welfare-2/looking-ahead-the-nations-child-welfare-systems-after-coronavirus/41738

Yang, M. (2015). The effect of material hardship on child protective service involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 41, 113-125.

One Comment